Kuhle Wampe and the Great Hertha Thiele

"It begs the question: why do people no longer make cinema like this?"

How this film flew under my radar for all these years is a mystery to me, especially since I am very familiar with the work of both Bertolt Brecht and Hertha Thiele. Kuhle Wampe was made in 1932 by Slatan Dudow, a Bulgarian director who had spent time in the Soviet Union and soaked up all the Eisenstein he could, but the influence of Brecht, who co-wrote the screenplay and directed the final scene, is unmistakable. The film is overtly political and radical in both form and content, and it begs the question: why do people no longer make cinema like this?

The story is essentially melodrama. A young woman named Anni, trying to survive in a Weimar Republic crippled by unemployment and corruption, gets knocked-up by her boyfriend and doesn’t know what to do. But unlike a lot of melodramatic agitprop (think Xie-Jin’s incredible film version of Red Detachment of Women), the film moves far beyond the kind of stereotype and exaggeration that fuel the hyperbolic nature of those sorts of narratives. There is stunning location footage of Berlin shot in natural light, and it’s cut together in a fashion that recalls not only Eisenstein but also Vertov’s Man With A Movie Camera. One of the most inventive formal components involves the way Brecht and Dudow create a remarkable counterpoint between sound and image, a sort of dialectical loop illustrated perfectly by the scene where Anni’s father reads a salacious description of a nightclub performance by Mata Hari while we view images of produce and skyrocketing food prices. It’s the kind of stuff we won’t see again until Varda, Godard, Straub-Huillet, and it’s even more powerful slapped right into the middle of a film shot in 1932.

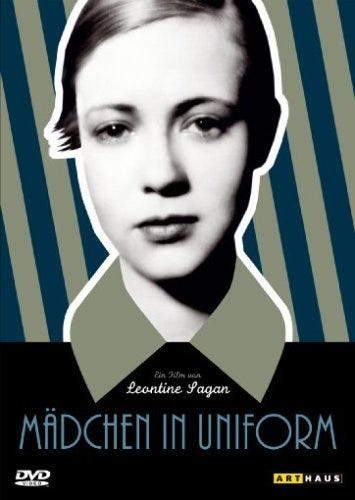

And then there’s Hertha Thiele – luminous, sensual, independent, and radical in every sense of the word. Hertha had caused a scandal a year earlier when she starred in Leontine’s Sagan’s Mädchen in Uniform, an early (the earliest?) example of queer cinema, which deals with lesbianism in a girls’ boarding school.

Thiele made both Mädchen and Kuhle Wampe on the eve of Germany’s descent into fascism and she would eventually have to leave the country altogether after more or less telling Goebbels to fuck off in 1936. What she reminds me of most, and what Kuhle Wampe’s final scene reminds me of as well, is how close Germany was to moving hard left, towards a real workers’ state, before the left fractured and things went horribly awry. It reminds me of where we are now, and it demands that we ask ourselves if there isn’t a place for filmmaking of this kind, especially in a world that is so eerily similar.